IceTowers is a great game to get you started with pyramids and to take advantage of their stackability feature; a high-speed game played without turns on any flat surface. It's often seen played in the extra-large version at conventions and events.

[First published in GAMES magazine, October 2005 edition.]

IceTowers is a great game to get you started with pyramids and to take advantage of their stackability feature; a high-speed game played without turns on any flat surface. It's often seen played in the extra-large version at conventions and events. |

A few miles off the Beltway in College Park, Maryland, an ongoing experiment is taking place. This is the home base of Looney Labs. Its chief researchers are Andrew and Kristin Looney, and their not-so-silent partner, Alison Frane.

The Looneys freely admit that they’re wacky pack rats, and a step inside the door of Wunderland Earth is proof aplenty. Every spare unit of emptiness is occupied by an artifact, a gimcrack, a gewgaw, a collage, a montage, a set of game pieces, a conversation starter. Hundreds of board games overflow the shelves in the game room. A model train makes a loop along a track mounted around the perimeter of the kitchen ceiling. A green parrot squawks out a greeting. But the stereotypical pack rat is a hoarder; the Looneys are collectors and arrangers. The place isn’t untidy. It’s small, it’s crammed to the rafters with stuff, but every object appears to have its place and was obviously deposited in its place by design.

Looney Labs has a knack for creating highly original games with unusual themes and titles, including Chrononauts, Cosmic Coasters, Nanofictionary, and Are You a Werewolf? |

To start any small business and have it grow and succeed takes some nonfiscal assets. Discipline, organization, and patience are near the top of the list. Then comes energy and enthusiasm, belief in the product, and marketing instinct. To start a game-design business, add talent and creativity to the mix. Looney Labs (www.looneylabs.com) is not a he-does/she-does operation; all three partners do all--with the help of lots and lots of friends.

Andy and Kristin met at NASA in the 1980s, where both were gainfully employed in chip design. If this sounds like brainiac work, well, it is. Andy is known for writing highly readable code; as he proclaims on the Looney Labs webzine (www.wunderland.com), “I spent over 10 years of my life working as a professional programmer…I am not currently using these skills to make my living, and if all goes according to plan, I never will again.”

Kristin was working on gate arrays and telemetry systems and task management. (If you need to know what these are, stop reading now; we’re not going there.) Then she got involved in the design of an Internet before that term existed. She held the title of fastest cube-cracking female in the West--well, okay, in the world--at the height of the Rubik’s Cube craze. And she has proof: When the TV show That’s Incredible set out to find a champ, Kristin came in fifth, behind four other male geeks.

In his sci-fi novel The Empty City, Andy Looney describes a pyramid game without quite giving the rules. His childhood friend John Cooper figured out a playable game based on the concepts in the book, and the first Icehouse set was born. |

“We were sharing an office,” Kristin says, “and one of our biggest influences back then was Cosmic Wimpout. Classic, classic game.” Independently of each other, they had become fans of a cool little hippy-dippy portable dice game. Five dice with dozens of mind-boggling rules that make it impossible to finish a game in five minutes. (A high point of Cosmic Wimpout folklore was in 1979 when the Grateful Dead politely but firmly asked Wimpout fanatics to stop stickering their tour bus.) The bond began to cement over the roll of the dice, the office romance took off, and the Looney Labs experiment entered Phase 1.

Andy was writing (as he does to this day, working all night and going to bed when the sun rises) and forming the basic bricks and mortar of a now-famous game system called Icehouse in his mind. In his sci-fi novel The Empty City, he describes a pyramid setup played by the characters in the book--but not quite playable by the reader. It was a notion that needed fleshing out. Enter several game-playing colleagues, including childhood friend John Cooper. It was Cooper who first figured out a playable game based on the concepts in the book, and the first Icehouse set was born.

The creative team of Looney Labs: (left to right) Kristin Looney, Andy Looney, and Alison Frane. Andy and Kristin met during the 1980s at NASA, where both were employed in chip design. |

The Looneys’ office at NASA started sprouting pyramids. Wood pyramids. Clay pyramids. Resin pyramids. At Wunderland Earth, another book appeared on the shelves: Steve Peek’s The Game Inventor’s Handbook. “We read that over and over again. It was a scary book,” says Andy, “Basically, it said that if you’re thinking about becoming a game inventor, you’d be better off taking all your life savings and going to Vegas and plunking it down on a single spin of the wheel. You’re nuts to go into this. But if you insist, here’s how.”

Peek’s book stressed the importance of bringing fans into the fold, and that advice was not lost on Kristin. “Word-of-mouth is all-important in building a game business,” she says. “It’s all about somebody playing the game, liking it, and wanting a copy of their own.” Her evangelistic energy is infectious: “Every single one of those people who goes out and teaches it to a few more people is helping,” she says.

So the very first thing the Looneys did back in 1989 was publish 100 signed and numbered Icehouse sets. Included with each set was an insert. “If you like our game,” it read, “the biggest favor you can do for us is help us promote it.” That was the beginning of the now-populous Looney Labs fan base. A mailing list grew; contacts were maintained the snail-mail way; the Looneys went to sci-fi conventions and game tournaments, spreading the Icehouse message. They took what they learned from the Cosmic Wimpout designers (really, just a bunch a friends and fellow Deadheads) and started a newsletter called Hypothermia. The Rabbits would come later.

Pyramids in the original Icehouse sets were solid. The addition of piece-stacking capability has made Icehouse into a much more flexible game system that can be used to play a wide range of games. |

Icehouse had its fans, and it rested on its laurels for seven years. It used solid pyramids, but the manufacturing was always a headache. Finally, the Looneys decided it was time. “We said, ‘We’ve got to come up with other games to play with the pyramids.’”

That first Icehouse game didn’t use stacking. “I invented IceTowers, which used stacking pieces, before we had stacking pieces,” says Andy. “I did the design in one night and showed it to Kristin the next morning; she made me a set, and when I got up we played it.” It’s now one of the most popular games played with the Icehouse pyramids.

Today, Icehouse has gained fame as a game system--not as an individual game. This “system” concept is something that has taken the Looneys 16 years of proselytizing to stamp in the minds of game fans. Unlike the Piece Pack, however (See GAMES, July 2004), it didn’t come cheap. Their first effort, the Martian Chess Set, included a bunch of plastic pyramids and the rules to four games--IceTowers, Zarcana, Martian Chess, and IceTraders. (In 2001, Icehouse: The Martian Chess Set won an Origins Award for Best Abstract Board Game of 2000.) It retailed for $35. On the company’s Web site, fans snapped up 600 copies in the first month. In the stores, it flopped.

Why? People didn’t get it. It wasn’t just about the plastic pyramids. It was intellectual property that came after hours and hours of playtesting. Ironically, you can buy a set of punch-out pyramids on the Looneys’ Web site today for $5, and read the rules to the various games. But once you get hooked, you won’t settle for the cardboard version. in fact, as one reviewer notes, “Paper Icehouse is to the gaming community what shareware is to the PC community. It is a limited version of the full-fledged thing. You can play most of the games listed on the Looney Labs Web site with it, but the pieces are prone to falling apart, and there are some games which require stacking of the pieces, which is impossible with the paper set (Unless, of course, you want to go through each and every piece, cutting out just the right size square from the bottom. With 60 pieces, that could take a while.”

The “system” concept did eventually sink in. The proof? For one thing, sales. For another, the fan base. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, students of game design read a textbook titled Rules of Play (by Katue Salen and Eric Zimmerman). The glossary in back lists arcade games, board games, card games, computer games--and Icehouse games. “They totally understand,“ says Kristin. “It just took time.” The Icehouse entry reads:

The pyramids of the Icehouse set are a great example of a well-designed game system. They can be physically configured in any number of ways: stacked on top of each other, aimed at each other like arrows, organized into patterns, or distributed randomly--different Icehouse games take different advantage of these material affordances. The number of pieces and distribution among the three sizes and four colors also determines the formal relationships and logical groupings that can be expressed by the organization of pieces. The Icehouse set component elegantly embodies a flexible yet expressive set of potential formal and experiential relationships.

| New ways to use the Icehouse concept are being created all the time. The Ice Game Design Competition is open to all original, unpublished games that make use of Icehouse Pyramids; the fourth contest ran from April 23 to June 5, 2005. Read the results at www.icehousegames.com/contest/. |

The book Playing With Pyramids, authored by the Looneys, John Cooper, and others, describes a dozen different games for Icehouse pieces. Four of them require a chessboard; others use stones, dice, coins, cards…or nothing but the pyramids themselves. The rules themselves seem deceptively simple; the strategy fills a small book.

In order to play the Icehouse games, you need at least two “stashes” of pieces. A standard stash consists of 15 uniformly colored pyramids, five each of three different sizes. One game, Volcano, can only be played if you have six stashes of stackable pyramids. IceTowers, arguably the most popular Icehouse game, has no turns and no board. Players stack their pieces on one another’s towers, take pieces from the middles of towers, and split towers in two. Although there are no turns, neither speed nor dexterity is required; three to five players take about 10 minutes to play a game, longer as they improve. Then they play another…and another.

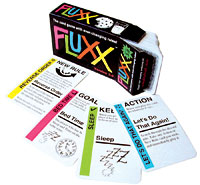

With Fluxx, the artistic talents of Alison Frane came into the fold, and the Looney Labs duo became a trio. The art took on more sophistication; the creativity bloomed. Ideas that had been simmering came to a rolling boil. The Frane flair for wordplay is tracked all over looneylabs.com. In fact, the three-heads-together collaboration has been fruitful, and Fluxx was the hit that got Looney Labs on a roll.

Fluxx, which won an American Mensa design award in 1999, uses an 84-card deck with four kinds of cards: Keepers, Goals, Actions and New Rules. It starts out simply enough: draw a card, play a card. But when a New Rule card appears, everything changes. New Rules may change the number of cards drawn and played per turn, the number of cards you hold in hand, the number of Keepers you can have, and more. |

A game of Fluxx can be played in 10 minutes, or it can last an hour. It’s been argued that Fluxx is a tactical but not a strategic game--that is, there’s no way to plan ahead. The designers are the first to admit that luck does play a role in Fluxx. But it’s easy to learn, quirky, and random--it’s the card game with ever-changing rules. Kristin says that it has the all-important “one-more-game” factor. “That phrase--‘C’mon,let’s play another’--is music to a game designer’s ears,” she explains.

Fluxx won an American Mensa design award in 1999, but it’s a surprisingly accessible “nongamer’s game” that appeals to a variety of people. Its 84-card deck uses four kinds of cards: Keepers, Goals, Actions, and New Rules.

Fluxx starts out simply enough: draw a card, play a card. But when a New Rule card appears, everything changes. New Rules may change the number of cards drawn and played per turn, the number of cards you hold in hand, the number of Keepers you can have, bonuses for players who have particular Keepers, and more.

On boardgamegeek.com, Fluxx is controversial. “More like a virus than a game: mutates but never dies,” writes one gamer. There’s no denying, however, that the fans are out there. “If you want a very light, random-heavy card game (but still with plenty of choices and a small amount of strategy), then Fluxx is for you,” advises another. “Fluxx is mostly about waiting for an opportunity to win. That said, it can be a fun ride, especially with the right crowd.”

Eco-Fluxx, a new twist on the classic, will hit store shelves in October. Skillfully illustrated by Frane, Eco-Fluxx is a joint effort created with a lot of input from the summer-camp kids she counsels. A percentage of the game’s profits will go to environmental causes; if you regularly read the Looney webzine, this should not surprise you.

Finally, there’s another joint effort, Stoner Fluxx. Ask your retailer--it could be in the store, but might be under the counter.

This 136-card game with a time-travel theme is, according to Kristin, one of Andy’s best efforts. It won a Parents’ Choice Award in 2001 (because of its history theme) and an Origins Award the same year. In Chrononauts, you travel through time (backward or forward) with a unique identity and a secret mission. Imagine snatching up a priceless work of art just before history records its destruction, or altering the course of history itself. And is that the version of reality that you came from originally…the one you must return to in order to win?

Andy Looney has won three Origins Awards for game design from the Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts and Design: Best Traditional Card Game for Chrononauts (2000), Best Abstract Board Game for Icehouse (2000), and Best Abstract Board Game for Cosmic Coasters (2001). |

To start a game, the timeline is placed on the table in “real” order. Timeline cards are of two types—linchpins and ripple points. The linchpins in turn cause the ripple points to be affected, causing a paradox in time that needs to be repaired (and if 13 paradoxes are created, the space-time continuum collapses and everyone loses). Patches are placed over these paradoxes. Like all Looney card games, the basic turn is draw a card, play a card. Here you could invert a linchpin, patch a paradoxed ripple point, play an artifact, or play an action card. It’s all packed into a fast, easy Fluxx-style card game that takes you to the beginning of time and back again in about half an hour, and you don’t need to be a game geek to play it.

Nanofictionary is all about telling tiny stories, as the name implies. Four plot devices come into play: a Setting, a Problem, at least one Character, and a Resolution. Players combine and recombine these elements to create the best story they can, while other players mix things up with Action cards. No assembly--but some imagination--is required.

The game progresses through three separate phases. In the Writing Phase, everyone develops a story outline by collecting the four types of plot devices. This is followed by the Storytelling Phase, when players take turns telling short stories based on their cards, embellishing as needed to unite and explain the elements on the cards. Finally, the Awards are given. But there’s more to it: You can Brainstorm new ideas, Plagiarize from other players, and Uncrumple old ideas out of the discard pile.

If a scenario immediately springs to mind when you think about “Mischievous Children” in “The Shopping Mall, Just Before Closing” having a “Disagreement About Something Unimportant,” but “Duct Tape Saved the Day Again,” you’ll have a great time with Nanofictionary. It bears not the least resemblance to the well-known party game Pictionary.

One boardgamegeek (obviously a “serious” gamer) puts it this way: “To me, this game fits well as a break or an end to a marathon gaming session, when players have stretched their brains every which way for the last 18 hours, and want something less competitive and strategic.”

It’s all about the company you keep. Andy, Kristin, and Alison, despite their brainy credentials, are not selling games that send players deep into an introspective maze of move-planning. They firmly believe that gaming should be social as much as cerebral, and the imagination factor is huge; games bring people together and away from their televisions and computers. It’s all about the fun. A roomful of silent, frowning, head-scratching players is obviously not playing a Looney creation.

The Mad Lab Rabbit program was officially launched on the Looneys' weekly webzine in November 1999. By that point, the fans were already in place; the games had been around for 10 years, and though they were only just beginning to appear in stores, they'd been sold at sci-fi and gaming conventions and via mail-order for years. |

The Looney community is populated by creatures known as Mad Lab Rabbits. If this anthropomorphic marketing gimmick is too whimsical for the hard-core strategy gamer, it serves a vital purpose in ensuring the survival of this small, kinder, gentler, “funner” company. Kristin, who has no formal marketing training, understands branding. Unlike the book-publishing industry, the game world hasn’t yet been federated by the big chain stores. A small outfit like Looney Labs still has a fighting chance of getting its product on the shelves--if the buzz is kept alive.

The idea of cultivating a fan base is not unique. Steve Jackson Games has its Men in Black; Cheapass has its Demon Monkeys. But the Mad Lab Rabbits are special: Their mission is to multiply. They get incentives, but not freebies--”We don’t want to shoot our retailers in the foot,” Kristin explains.

Rabbits come in a variety of breeds. Blab Rabbits teach the Looney games to friends and family members; Demo Rabbits go to stores and special events to spread the word. They also organize local tournaments, set up game nights, and preach the Looney Game Gospel--for which they earn rabbit points to be spent on the Web site. A group of fraternizing Rabbits? A Warren, natch.

Other furry fans, affectionately referred to as Test Subjects, are people who enjoy the games, but don’t yet call themselves Rabbits. Rabbits run the gamut of devotion from lukewarm to ardent, but the majority--judging from the rabbit ears seen at conventions--are pretty enthusiastic.

Every Thursday at Wunderland Earth is game night, when a dozen or two dozen or as many as 30 friends sit down to play. This is the inner rabbit circle--the Wunderland Toast Society.

Rabbits gather each year in Columbus, Ohio, at the Origins Game Expo—a huge event at which the Looneys run a "convention inside a convention" called "The Big Experiment." They also host annual tournaments for all of their games; Rabbits from all over make the pilgrimage.  |

The Origins International Game Expo is the second largest and longest-running gaming tournament convention in the United States. Manufacturers come to Origins to show off their wares, but for a trio of game designers with a whole lot of friends, it’s the time to touch base. This year, as in previous years, the Looneys and their local Rabbits (in lab coats, of course) were front and center, hosting The Big Experiment.

The Big Experiment takes place in a big space, with big pyramids. Kristin tells the story of one group who started out the weekend at the Pokémon tournament…”where there’s all these kids--serious and angry and mad. They went over to the Looney Labs space where it’s friendly and fun and relaxed and wonderful, and they looked at these two spaces, and said, ‘Screw this,’ and played games with us all weekend.”

The fans come in all ages. They range from high-school and college kids to 40-year-old computer geeks. “We’ve got kids bringing their parents into the gaming fold,” says Andy. Adds Kristin, “We have fans who I’ve never met and don’t know from anything that’ll write me a check for $30,000. It’s a good investment and they know that. They’re getting better interest than they’d get from a bank, and we get the money we need that the bank won’t give us.”

“Banks have this pesky thing they need called collateral,” adds Andy.

Not that the company is in trouble: The days when the mortgage payment went on the credit card are over. Even with four Origins Awards and three U.S. patents, the Looneys are still very much at it, constantly testing new games and inviting the Rabbits to have a go at them. (Currently in the beta stage is a game called Just Desserts, and Eco-Fluxx is in the playtesting stage.) Then there are the Retailer Rabbits. Needless to say, Kristin has been making friends with her retailers since the beginning.

“We say all the time,” says Andy, “that we’re standing at the tipping point. We’re right there. Eco-Fluxx could do it. A mass-market account could do it. Our warehouse can handle it. All we need is volume.” A couple thousand rabbit-eared friends can’t hurt, either.

| ICEHOUSE GAMES | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Players | Extra Stuff Needed | Style |

| Ice Towers | 3–5 |

none |

turnless, stacking |

| Thin Ice | 2+ |

none |

building, party |

| Zendo | 3–5 |

60 stones |

inductive, puzzle |

| Martian Backgammon | 2 |

dice, 3 coins |

luck-based, race |

| Volcano | 1–4 |

none |

puzzle, positional |

| Martian Chess | 2,4 |

chessboard |

colorblind chess |

| RAMbots | 2–4 |

chessboard |

program, predict |

| Pikemen | 2–4 |

chessboard |

pointing chess |

| Zagami | 4 |

chessboard |

consume, exploit |

| Icehouse | 3–5 |

none |

turnless, strategy |

| Homeworlds | 2–6 |

cards |

space opera |

| Gnostica | 2–5 |

tarot deck |

territorial, war |

| AQUARIUS |

|---|

|

This groovy 60-card game is played kind of like dominoes, with each player trying to win by connecting seven panels of one particular element. Goal cards determine which element each player is going after, and Action cards allow players to shake up the action in five different ways. The game is fast, fun, colorful, and easy to learn. To win, you must connect seven panels of a single element (Earth, Air, Fire, Water, Ether). There are a number of ways to play Aquarius, all explained at www.looneylabs.com: Standard Rules |

| COSMIC COASTERS |

|---|

| You’ve transported a ship to an enemy planet. Now what? This “teleportation combat game” for two players (though variations exist for three or more) is played with coins on custom bar coasters. Suggested retail price is a measly $5.00. Yes, these are real bar coasters, intended for repeated use in beverage-intensive situations. You can get them soaking wet and they’ll be fine when they dry out. Each coaster is a gameboard despicting four NASA images of the major moons of Jupiter (Ganymede, Io, Callisto, and Europa). Each moon carries a unique special power (Stinging Defense, Teleport Inhibitor, Warning System, and Rapid Transit); rules of play are on the back of the coaster, in case you forget. Each player receives two coasters: The first is used as a gameboard, loaded up with a fleet of seven coins or tokens, and the second is kept next to it, facedown. (This serves as both a rules reference and an indication of the player’s special power. It can also serve as a coaster for your beer.) Cosmic Coaster won an Origins Award as the best abstract strategy board game of 2001. |